Paul Is Dead: Perfect vs. Great (Known Unknowns #14)

My very smart friend Brendan Haley posted recently on Facebook that he was introducing his baby daughter to the music of Paul McCartney and Wings, but that he was going to hold off on teaching her The Beatles until her 18th birthday. Why? “There’s nothing more stifling to progress and creativity than the Beatles.” There’s then a 33-part discussion in the comments, which I stayed out of but read intently. About halfway through, Brendan said this:

I’ve always understood the importance of the Beatles, I’ve appreciated them throughout my life, and I will defend to the end of my days the genius of ”Tomorrow Never Knows.” But the Beatles are also one of the last things I’ll ever put on when I want to listen to music. Why? Maybe because of that “perfection” thing Brendan mentions. There may be such a thing as too perfect.

I think what puts me off about the Beatles – and this is no fault of their own – is that there’s no room for me in there. They don’t need me. My favorite stuff is the stuff that feels like a dialogue between artist and audience. One of the reasons I still love Stephen King, after all the supposedly (and, some, truly) superior writing I’ve read, is that there’s always a feeling of him sitting in the seat across from you, knee bouncing, as he tells you his latest story. When I talk to my students about what makes writing truly good, I talk about two things you really can’t teach in a workshop: narrative authority and reader involvement. Stephen King is a master of both.

By narrative authority (a phrase I borrow from Richard Bausch, one of our living masters of fiction), I mean the art of being in control of your story, your characters, your authorial voice. Stephen King has this in spades, and it makes up for a lot of what he lacks, particularly in his early stuff. It’s the feeling of “someone is driving this bus, and they sure as hell know where they’re going.” It’s not bravado or hubris, though an awful lot of writers seem to make this mistake. It’s a feeling that this writer has both totally committed to her story/characters/tone and is completely in charge. Fitzgerald’s first novel, This Side of Paradise, thinks it has Narrative Authority. What it has is a shitload of hubris, and it’s a ton of fun, but it’s not super-masterful in any way. The Great Gatsby really has Narrative Authority. It’s that thing where the reader feels, Wow, this writer is completely in charge here. (This is what I think people mean when they talk about “vision.”) It’s also that thing where you realize you’re going to follow this story wherever it wants to go. The Beatles, it should be said, have tons of narrative authority. They’re never not in control of their material, you never question who’s driving this bus, and even though there are four singers and three songwriters, it always sounds like the Beatles.

This brings us to the second piece of truly good writing: reader involvement. By this I mean that a piece of fiction, whether you like it or not, only works when there’s a communion between writer and reader. I think this is where the Beatles leave me out, though I have listened to them with fascination and awe since I was ten. (I still have my dad’s vinyl copy of Sgt. Pepper.)

I have a separate post planned about this idea of communion, but at its core, it means there’s a give-and-take. It can’t be any other way. It works like this:

- As a writer, I think of characters and a situation in my head.

- I translate these as best I can into words.

- You then read the words – maybe later that day, maybe decades from now (if I’m lucky) – and retranslate the ideas into your head.

Now: Does your version look and feel exactly like the version in my head? It doesn’t, and it can’t, because this is not Wonkavision. Our only means of transmission is the words. On the face of this, it would seem that writing and reading prose is like using a telegraph in the age of Skype. (Note: William S. Burroughs once said a movie script isn’t the same as prose fiction because a script is a set of instructions. I’d argue that, in the end, that is what they both are.)

But when you’re in control of your narrative – bingbingbing! Narrative authority! — you can maximize this relationship with the reader. Any writer can write something and make that idea appear in a reader’s head. They’re words; string them together in a coherent fashion, and they’ll do that work all by themselves, for better or for worse. But great writing makes explosions of images, senses, and experiences in a reader’s head. And these explosions can permanently alter the way both writer and reader understand or perceive things. Between you and me, we are creating special new worlds, we are making lives happen. We need each other to do this.

But then there’s this idea of Perfection. I think a lot of what gets called Important Fiction falls into this trap. They’re too much like well-crafted adaptations of great fiction. This is surely gonna kill Jonathan Franzen’s entire career, but while The Corrections is a really good novel, it has a serious humanity problem. When Franzen writes, he does so beautifully and deeply, and he absolutely includes lots of insight into the problems of personhood. But he also does so at a weird distance. With Franzen, it’s like a ‘50s sci-fi alien writing about “these things we call hu-mans.” It’s a limited version of communion, in that I’m in there alongside Franzen, watching these characters. But I’m never in the characters. Franzen, like a realtor, never lets me out of his sight.

There’s also the pursuit of The Perfect Sentence, which can become all too apparent as an end of itself. Richard Ford’s Independence Day is full of perfect sentences, yet not one holds a candle to Denis Johnson’s line about “the water of inlets winking in the sincere light of day, under a sky as blue and brainless as the love of God.” Why? Because, to put it doubly crudely, you can hear Richard Ford working like a motherfucker to get himself off. (Or to impress John Updike.) I’m under no illusion that Johnson’s line came to him spontaneously, but it sure feels like it did. And those are the best moments in fiction, aren’t they? Where you feel a sense of discovery along with the writer? It’s like jazz, where you can hear the players suddenly click into an idea, and you can almost see them smiling to each other, like: “Yes, THAT.” And maybe they hit that same idea in rehearsal and liked it then – but now, with an audience present, and with an audience reacting, the idea becomes a shared excitement. That’s also reader involvement. That’s communion.

Also, let’s not undersell Denis Johnson’s narrative authority: That line is beautifully crafted and has a shitload of personality. I like the person who comes up with that line. I want more of that, and boy does he deliver.

None of this is a new idea. “Perfect is the enemy of the good” is a phrase that appeared on many a fortune-cookie message in 1772. So here’s what I’m saying about perfection– as a practitioner, as a teacher, as a reader:

Worry about perfection only in the pursuit of transmitting that thing in your head. Get it so that it stops being like watching something happen and starts being an experience. But in the big picture, please don’t try to be perfect. Try to be great. Be a little messy. Be a little weird. Let it be a push-and-pull between writer and reader: Here’s what this means, isn’t that crazy? Are you liking this much as I am? No? You’re gonna love this next part. Make no mistake: The writer is the driver of the bus. But a) a bus needs passengers; and b) you have an obligation in all situations to be a good host.

More: Be personal in your work, even if the work itself isn’t (on its surface) about you. Make sure, in fact, that it is personal. We can tell the difference, and we can feel you not caring. Similarly (but separately) be personable. I want to like your characters, but I also want to like you. People who read Martin Amis or Virginia Woolf or Junot Diaz read them because they like that voice, the person on the other end of the telegraph line. Again: Stephen King.

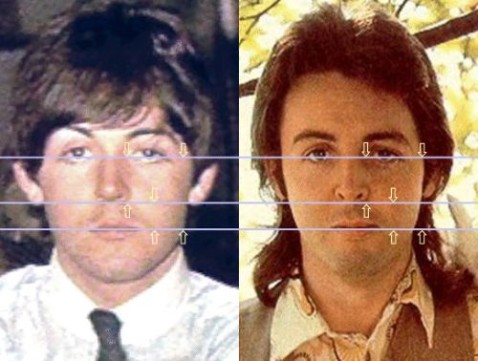

Listen to McCartney’s songs on Sgt. Pepper and Abbey Road, and then listen to his early solo work, including Wings, and tell me he hadn’t come to these same conclusions. If there’s one thing post-Beatles McCartney doesn’t get enough credit for, it’s his looseness. There’s the feeling that he knew what he’d done with the Beatles, he knew he’d helped build the Egyptian pyramids of popular music, and now he was going to start making music for the fun of it. This McCartney is still an obsessive and an innovator, but you actually can hear him enjoying himself again. (This is often categorized as “tossed off,” exhibit A being the world’s most hated Christmas song, “Wonderful Christmas Time.” Please be my guest and try and write something as catchy as that song. I’ll wait.) If you think about it, Paul did die, though not in the way believed by the conspiracy theorists, and not in the way Lennon meant in “How Do You Sleep?” For all the difficulties Lennon clearly had with being a Beatle – and after, with having been a Beatle — I think McCartney shed it with surprising ease.

The difference between these modes of pursuit – the perfect and the great — is ultimately the difference between essential and vital. Essential is something you must hear and know in order to be properly informed. The canon, in other words. And you can love essential things, and sometimes they can even love you back. Vital, though, also implies necessity — but with an urgency about it, a liveliness: Holy shit, you’ve got to experience this thing now. The Beatles are essential. McCartney’s Ram is vital. (Queen, Bowie, and Sly & the Family Stone are both.)

Guys (and it’s always guys) who aspire to be Great American Writers are aspiring to be essential. A million times over, I’d be far happier to achieve vital.

There is so much to ponder in your post that I certainly would never be able to collect my thoughts about it 30 seconds after reading it. However, I will say I enjoy McCartney’s “Wonderful Christmas Time” in much the same way you describe it, and often use that feeling to talk about so called “bubblegum pop” that so many call “guilty pleasures.” So far, I’ve never read a good description/definition of why someone likes a song; you just do because it’s pleasant to your ears/head. At the very base level of existence, no one can “make” me not like something, no matter what he/she says about it. Why should I feel guilty about that?

This might have slightly gone off the tracks and now has nothing to do with what you’ve written. I do that a lot. Also, this might be just trying to justify my enjoyment of Britney Spear’s “Toxic” with myself. Carry on, and thanks for the post.

Hi Matt –

Perhaps a key ingredient of “vital” is a sense of vulnerability of the artist. The Beatles are so confident, controlled, and polished that there’s little sense of their vulnerability. They’re impervious. Denis Johnson reads like he’s in control, but riding the edge. Same as Junot Diaz, The Pixies, Thelonious Monk, or a painting like Weeping Woman by Picasso. They have authority–I’m not nervous for these artists–but there’s an excitement in the work that feels like risk, like something brutal. They’re revealing a depth and rawness that we can relate to, even if it may be ugly.

Pete

Chris – I like where those tracks have gone, though. I have plenty of “guilty pleasures,” but like you, I don’t really believe in that concept. I love, completely, the music of No Doubt. I love AC/DC, and not just when indie bands suddenly decide AC/DC is worth considering. I love Jethro Tull, for god’s sake. So I hear you. And the thing that McCartney Christmas song points out, that I think some people don’t like, is that they hate it because it’s so goddamn catchy. And that is a kind of genius, just as what it took to write (and play!) “Blackbird” is a kind of genius. They don’t often co-exist, those kinds of genius, so when we see both in a guy like McCartney, it’s jarring, and thus it means he’s “lost it,” or has stopped giving a shit. But you’re right — in the end, we like what we like.

Pete! I like this. I’m definitely attracted to — and energized by — those works where you think: Holy shit, this shouldn’t work. Or: This is going to collapse any second, right? I love the films of Paul Thomas Anderson for this reason. Or The Godfather — I can’t imagine going to see that for the first time, because the whole time you’re watching it (even now) you’re thinking, Oh, there’s no way he’s going to pull this off, it’s too huge. And, of course, he does. To extend further the bus driver analogy, you’re on the bus, you know who’s driving, you know she’s in control — and then she takes you off the highway and onto a winding mountain road with no guard rails. And you should be screaming, but you trust her.

That’s why so much experimental stuff falls flat for me — it’s all treacherous mountain road, but I have no faith in the driver. Jennifer Egan’s built up a lot of good will and trust in A Visit From the Goon Squad before she steers into that Powerpoint chapter, and then further into the futuristic(ish) final chapter. By that point, she’s taken some risks and yet shown she’s someone you want to travel with. Dan Chaon dares you to find his characters upsetting and troubling, etc., but he also demonstrates he knows what he’s doing with them. (First and foremost by presenting them as real people, crafted with a superior author’s empathy.) Melville, too, in Moby-Dick. This was not one of the million-and-one high-seas adventure tales that’d been published by that point, and by just a few pages in you’re eternally grateful for that.

And part of all this is the vulnerability you talk about. The bus driver saying, “People, I need for you to trust me. This is something I just HAVE to do. And it’ll be worth it for you, too.” So it’s a game of trust between writer and reader. And that’s key.