P.O.V. part I: The Who and the What

Richard Ford, interviewed in the Paris Review, told a story about letting friend and poet Donald Hall read a draft of his second novel — a draft Ford assumed was finished. He met Donald Hall for dinner and Hall said he hadn’t liked the manuscript. Ford was devastated. Then he went back, changed the point of view from first to third person, and went on to publish the book, The Ultimate Good Luck. I still haven’t read it, because I’m a Donald Hall man, but good for Richard Ford.

Point of View is how we come to know a character and, thus, how we experience a story. It’s fairly important. Yet, like dental health and oil changes, we forget to remember P.O.V. until after something regrettable has happened.

Let’s look at the types of P.O.V., i.e., the Whos and the Whats:

First-person – I, me. I started a joke. Call me Ishmael. I am born. These are all first-person points of view. The first mode new writers often start writing in, but also perhaps the most difficult. I’ll get into why that is in the next post. Also, you can have first-person plural: Then We Came To The End and The Virgin Suicides are novels told from a collective “we” voice. The effect is odd at first, but then it becomes strangely intimate. More about that next time.

Second-person – You. The story is told as if from the reader’s P.O.V., but also to the reader. You always said you’d never do this again, but here you are. Again. What’s this, the third night in a row? The eighth? You’ve decided it’s better not to keep track. Famous examples: Bright Lights, Big City; Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl”; Choose Your Own Adventure books. Everyone will tell you not to do the second-person P.O.V., which seems like good advice until you read something fantastic in the second-person P.O.V. I say: give it a shot. What matters is what you put into it.

Third-person – He, She, They. The story is told by a narrator, but we may have access to the thoughts of one or more characters. This is where a lot of people just shut down and go, OMIGOD I CAN’T DEAL WITH THE DIFFERENT THIRD PERSONS PLEEEEAAASSSE. To which I say: stick with it. Figure ’em out. It’ll make a difference. So: the third-person P.O.V. modes are:

- Omniscient. This is thought of as an old-fashioned mode, because it doesn’t go into the characters’ heads, and because it doesn’t tend to stick with one character’s P.O.V. throughout. For this reason, we don’t tend to use it exclusively. However, I guarantee it’s used throughout almost everything you’ve read even recently. It’s simply the author pulling back and setting the scene, or making those authorial assessments that are sometimes necessary.

- Limited. This is probably the most common mode, the one you’ve seen all your life. We have access to a character’s thoughts and feelings, but we’re not in their head. This is why it’s often called “over the shoulder” narration, though picture more a camera that is somehow also linked to the brain of the character. (I’m sure there’s a Philip K. Dick story about this.)

- Close. This is the hardest to get your head around, but think of it this way: a character’s thoughts are the narration whenever this mode is employed. You’ve probably seen this mode so much in the last 30 years that you don’t even realize when it’s being used. Start to notice, and you’ll understand why it’s important. More about it in a minute, as it’s better defined by example.

Here’s the trick with third-person: Stop thinking of it as a complicated thing you need to be wary of and start thinking of it like a thing that shifts, like the gears on a car or the lenses in a camera. That’s all it is. Your story is the car, your story is the camera, and the modes of third-person P.O.V. are just varying degrees of power, intensity, or magnification. You want to just tell the basic details of what’s happening in a courtyard? Tell us in omniscient:

The crowd gathered and waited, young and old, for blah blah blah.

You want to get closer and tell us what someone in the crowd is thinking? Shift to third limited:

Jessa didn’t know why she was here. It was cold in the courtyard, she thought, too cold.

Want to get inside the character’s head and give us a feel for their thoughts? Go to close:

Why was she here? It was cold. Too cold. Still: better to freeze her balls off in this courtyard than to go home.

Why is that last one close, versus limited or omniscient? Because the narration there is a direct feed from the character’s head. There are no quotes around it, no “she thought”s, nothing separating it from the rest of the narration. It is in the language of the character herself — and, indeed, it sounds like dialogue or first-person narration: “Why am I here? It’s cold. Too cold. Still: better to freeze my balls off in this courtyard than to go home.”

Which leads to an important question: Why would you use close third person when you could just put it in first-person? The answer: Options. Sometimes it just feels like a third-person story, and when it does, you want the option to move in and out of those modes as needed. Right now you want to be in her head in the courtyard, but next you might want to pull out and just show what’s happening. The whole time Stephen King was being dismissed as crap, the Big Mac of American fiction, he was, quietly, becoming a master of third-person modes. Read any five pages from Under The Dome and you’ll see him shift effortlessly.

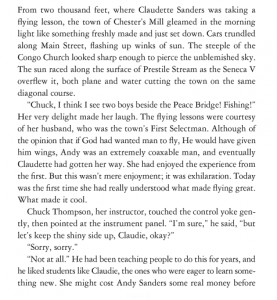

But I’m a control freak, and I don’t trust that you’ll remember to look at Under The Dome on your own. So let’s look right now at this screengrab of page one, from Amazon’s Look Inside feature:

First graph: omniscient. Second graph, after the dialogue: limited. Second graph, last sentence: close (“What made it cool” is her thought.) Third graph (“Chuck Thompson, her instructor”): omniscient. Last graph, first sentence after dialogue: limited. Last sentence (partial): close.

Here, King’s using his modes to a) set the scene (omni); b) give us the inner lives of his characters (limited); and c) give us the flavor of his characters (close). He’s also telling us, on page one, I am going to shift between different characters’ P.O.V.s and go in and out of their heads. He’s telling us the rules, in other words, and he’s doing it without being a present narrator. (Though, later, he’ll do that, too, directly addressing the reader.)

Here’s another page, chosen at random from, again, Amazon’s Look Inside feature. This one is from the point of view of another character, Junior, who’s just accidentally murdered a woman for not sleeping with him:

Look just at the first graph. First sentence, omniscient (or limited). Second: close. Third and fourth sentences: close. We’re in his head. Then we get his thoughts, amplified at us: Did I do that? Did I really? This is King’s choice to break up the close third this way, and I suspect it’s because the next graph is entirely in close third (Her fucking teeth. Those humungous choppers) and he’s jerking the wheel a little, making sure we’re paying attention.

Even the little words matter in close third. King doesn’t say, They were heading south down Main Street, toward THE booming sounds, he says toward THOSE booming sounds. (Emphasis mine.) Why? Because that’s what they are to Junior, THOSE booming sounds, the ones he’s heard but doesn’t yet have in any sort of context. P.O.V., you see, is character.

At the end of this two-page example, we then go to omniscient, backing out of Junior’s head exactly as we’re backing our way out of the scene: Nevertheless, Junior did not slow down. He skulked across the McCains’ backyard, unaware that he would have screamed guilt about something to anyone who happened to be watching (no one was). This is all narrator, telling us the deal from forty feet in the sky, even telling us that Junior is unaware of his appearance, and that no one is watching anyway. Junior can’t know these things, only the narrator can. This is omniscience.

Truth be told, most third-person fiction is written with a mix of these modes, though some writers in recent decades have done entire books in the close third person. (e.g. David Gates’ Preston Falls.) This post is about the Who and What of P.O.V. Next post, we’ll get into the When and Why. After all, I said you might choose third-person to have options, but then why would you write an entire novel in only the close third person instead of the first? Don’t they basically achieve the same thing? Not in the least, and I’ll tell you why…next time!

Photo Credit: pierofix via Compfight cc

Hey Matt,

Great take on POV. You keep it simple. I agree on its importance. I think that writing a story without considering POV is like taking a photograph of a car without thinking about using a camera.

Thanks, Brian! It’s one of those weird things people don’t think about. They have their comfort zones, and for some people it’s weird to think of writing in the third person, while for others it’s hard to imagine using the first. But you have to choose the mode that serves the story and the character(s), which is what I’ll get to in the next post. Thanks for reading!

Matt

Joshua Ferris’ “Then We Came To The End” is the most successful first person plural ever.

A large part of why I confine myself to nonfiction is because I get squeamish with anything outside first or second person.

Hi Matt, great post as usual. I recently heard George Saunders refer to close 3rd as “3rd person ventriloquist,” which struck me as a perfect term, and he is the master of it, I’d say.

Pete

MK – I loved the Ferris book, but I’ll confess that it took a while for the collective voice to feel natural to me. After a bit, I couldn’t imagine it without it, but it did take some sticking with it. But that book is such a great example of WHY to use a particular POV — which is, not incidentally, what I’ll be getting into in the next post!

(BTW, I have a hell of a time with the first-person, actually. It’s never felt natural to me!)

Matt

Pete – I love that and will commence using it immediately. Thanks!

Matt