LET’S STEAL FROM THIS! Bob Dylan’s “Self Portrait” and the Fun of Failure

LET’S STEAL FROM THIS! is a series of pieces looking at what fiction writers can borrow, craftily, from other sources. I will mostly look at television, movies, and comics, though the occasional literary work may squeak its way in, as will a song or two. LET’S STEAL FROM THIS! finds useful inspiration in unlikely places.

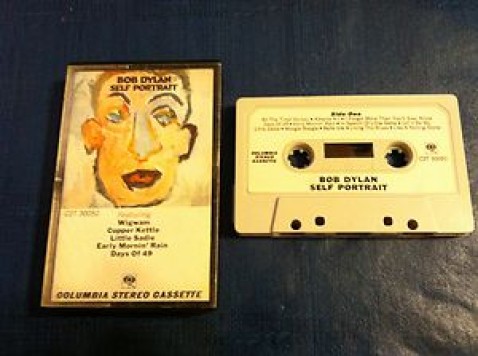

In 1988, my older sister lived with a guy who gave me, for my 18th birthday, two Bob Dylan cassettes: one containing his first two albums (a whole album on each side) and one of Dylan’s 1970 double album, Self Portrait. I haven’t seen this guy in decades now, so not only do I not know if he’s alive or dead, but I have no idea what prompted him to give an 18-year-old Bob Dylan/The Times They Are A-Changin’ AND Self Portrait in one shot. Perhaps he was going for value — those are eight LP sides jammed onto two tapes! Perhaps they were the only two Dylan albums at the store. Perhaps he was trying to point out the dangers of hero-worship! Or perhaps he was trying to wreck my goddamn mind.

Whichever he meant, it ended up being the latter. I didn’t know any better than to not like Self Portrait. It was years before I read or heard anything about how this was Bob Dylan’s crazy swan dive away from the 60s. In the years since, it has only grown into his personal Altamont, his most visible failure. (1973’s Bob Dylan rivals it, but that album was assembled by a pissed-off Columbia Records, so it doesn’t really count. Self Portrait was released by Dylan on purpose, and is the one most likely to make Dylan fans go, “Oh boy.”)

But like I said, I didn’t know not to like it. I liked the two early albums well enough, but found them a little sleepy, a little earnest. I’d bought Highway 61 Revisited for myself in high school, so I knew something of the classic-period Dylan. But even that, which I loved, seemed a little too serious, a little too wrapped up in pointing fingers and Telling It Like It Is. Self Portrait? It was fun. To me, it sounded like the guy who’d made the earnest records had got to a point where he just said, Screw it. I’m gonna make an album with a LOT of tambourine and a lot of echo and a lot of yodeling other people’s songs. Who’s with me? And from the sound of it, there are two hundred people in the studio who were with him.

Is it a good album? I don’t know. Not really. But does it matter? It has something to it that would keep showing up in the best of Dylan’s work throughout the next (very spotty) decade: It’s actually fun to listen to. Put another way: Self Portrait is not only the sound of Bob Dylan not giving a crap, it’s the sound of Bob Dylan determined to not give a crap.

Self Portrait was released in June 1970. It was followed just four months later by New Morning, which most Dylan fans think is just great. And it is. But it’s yet another kind of joke, because New Morning was recorded at the same time as Self Portrait. Self Portrait is the Goofus to New Morning‘s Gallant. It’s the Hugo to New Morning‘s Bart Simpson. It is assumed to be a total failure.

Let’s talk about “failure.” I put that word in quotes because I don’t believe it has the right to be a word. Which is tough, because the word is everywhere. For years, first in the geek community and (as always) later in the mainstream world, “fail” has been an easy, nasty shorthand for “you did something stupid.” If you search Twitter for any hashtag with some form of “fail,” you will not be disappointed. (Or you will be HUGELY disappointed. Not only is there a #momfail hashtag, but it updated with a new entry while I was checking whether there was a #momfail hashtag.) I’ve never been sadder with my kids than the first time I heard one of them say to the other, “Fail.”

But failure in art is nonexistent. It’s as useless a word as “evil,” which we’ll talk about in the next installment. It’s an easy word to use, and impossible to justify.

Failure assumes a standard of success. You can’t fail at something unless there was a baseline to meet or exceed, yes? But in the creative world, where’s the baseline between failure and success? Is it commercial response? Dollars? Because I hate to tell you: the worst Gerard Butler romantic comedy was probably still seen by more people than anything Nicole Holofcener has made. Does that make her a failure?

Can something be a failure if even one person likes it? Is it absolutely a failure if no one likes it? I think the answer is no for both.

So here’s what I think is the lesson of Self Portrait: If you make things — books, paintings, songs — you are already putting yourself in the path of failure. Or “failure.” Don’t just “fail better,” as Samuel Beckett said, because whether or not he intended it this way, I think that can be taken to mean “do a little better each time.” Well, screw that. How much time do you have left on this earth? To bring it back to Bobby Dylan, he not busy being born, etc. etc. So here’s what to steal from Self Portrait: Don’t fail better, fail BIGGER. Lose the sense of importance and take some ugly chances. You may surprise yourself and others.

Sidebar: This may explain why I like only the nonfiction of David Foster Wallace. I do not enjoy his fiction! I’m sorry! I can always hear him trying, can hear him calculating the angle and force of his serve, if you will. Some people like that, but where they see Wallace as a taker of big chances, I see him as a writer who’s never able to shake the need to Be Very Important. (See also: Franzen, J.) Yet in Wallace’s magazine pieces, I don’t feel like he’s trying to be as momentous or as shrewd, and it pays off. But to each his or her own.

Here’s the coda to the story, and I put it here because it shouldn’t matter: Dylan himself says he did Self Portrait as a goof, a not-uncruel fuck-you to the people in his audience who needed him to be The One*, every time. Then he put out New Morning a few months later, for whomever was still left. He told Rolling Stone in 1984: “Well, [Self Portrait] wouldn’t have held up as a single album—then it really would’ve been bad, you know. I mean, if you’re gonna put a lot of crap on it, you might as well load it up!”

So the joke was on the audience. Except for me, 18 years later! Even without knowing it was hated, or how it was intended by its maker, I liked hearing the super-serious Dylan having fun, trying crazy things, making a mess. And “All the Tired Horses” and “Wigwam” make me wish Dylan had gotten more in touch with his weird side, instead of easing ever more toward the role of aging swamp-blues-guy. Do I listen to Self Portrait every day? God, no. But it actually enhanced my appreciation of Bob Dylan, and I’m glad it exists. That is the opposite of a failure.

And then there’s this: Just this year Columbia Records’ ongoing Dylan Bootleg series released Another Self Portrait — 52 tracks of demos, alternate versions, and outtakes from the Self Portrait sessions. It’s an interesting choice, and I think it speaks to the fact that over the years, divorced from the concrete overshoes of Dylan’s own presence in the ’60s and even Dylan’s own provocations, Self Portrait has something to offer the listener. And shouldn’t that always be the case? Sometimes a joke reveals a lot more than the joker intends.

*I never understood the importance of Bob Dylan until my younger son started listening to the Beatles. When you hear John Lennon sing, “Gather ’round all you clowns” in “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away,” it’s like he’s just gotten off the phone with Dylan. Ditto for the Rolling Stones from the same era onward. And once you start looking for the Dylan influence, it’s hard not to find it. Any time you hear the words “clown,” “joker,” or “happening” in popular modern music, Bob Dylan should get ten cents.

Photo credit: ebay user bettys_a_mom, who was attempting to get $29.00 (+ shipping) for this cassette. To be fair, she says the paper insert, which I can tell you has nothing printed on the inside, is free of “bubbling” or other damage. Unfortunately, this auction has ended.